BACKGROUND

Data accuracy matters for child nutrition

Timor-Leste faces an incredibly high burden of child undernutrition, endangering child survival and long-term healthy development. Almost half of children under five are affected by stunting, one of the highest rates in the world. Poor nutrition, especially in very young children, can have irreversible consequences. Regular nutrition and growth monitoring is a cornerstone of early childhood healthcare.

Nutrition interventions work when they are delivered to those that need them at the right time. These services rely on data with a very high level of precision. Health workers collect anthropometric data—height, weight, and mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC)—then plot and analyze the data against globally accepted growth standards. Height-for-age, weight-for-height, and weight-for-age: Each measurement tells us something important.

Small mistakes in this process can lead to missed early detection of growth faltering or other signals of malnutrition in children. Such gaps have consequences: Misleading health assessments. Improper interventions. Delayed treatment. And ultimately, the possibility of irreversible compromises to lifelong cognitive and health development.

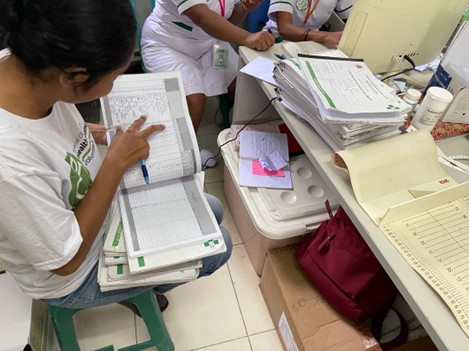

In Timor-Leste, Community Health Centers (CHCs) are the front line of the primary healthcare system and instrumental providers in child health and nutrition services. But CHCs face persistent challenges: limited staff training, high workloads, and lack of practical tools and systems. One result of these challenges is an ongoing concern about health sector data quality in Timor-Leste. Reliance on paper-based forms, registration books, and diagnostic tools means health workers spend excessive time looking for records or filling out forms manually. And manually plotting growth measurements into paper-based Maternal and Child Health Books is error-prone. Reliance on paper-based nutrition documentation led to discrepancies, duplications, and mistakes in the data that was reported and used to make critical decisions.

A typical CHC catchment area has hundreds of young children and might have more than 20 registration books at the health center. Health workers often had to search through many books to find a child’s record when they arrived for growth monitoring or treatment, which was time consuming and at times unsuccessful. Health workers also need to search these same books for monthly reporting. Nutrition Coordinators struggled to manually compile the data and accurately enter it into reporting forms for the national Timor-Leste Health Information System.